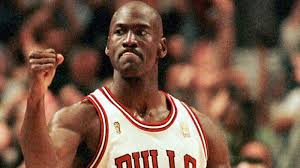

I’ve missed more than 9000 shots in my career. I’ve lost almost 300 games. 26 times, I’ve been trusted to take the game winning shot and missed. I’ve failed over and over and over again in my life. And that is why I succeed.

-Michael Jordan

Failure is a complicated word. Nobody likes even hearing the word, let alone having to experience failure firsthand. We avoid it at all costs. Failure can haunt your memories and make you cringe looking back. And try as we might, there is no avoiding failure. We are constantly failing. We at times wear it like an albatross, it weighs us down, and can sometimes deter us completely from continuing to pursue certain endeavors. While failure is not the most pleasant experience, it is one that we need to experience in order to grow and become better than we were. And the harsh truth is that sometimes you will have to put forth your best efforts for a long time before results become apparent.

Even though the word failure has such negative connotation, I don’t recommend substituting it for a less harsh sounding word, (ie. mistake, misstep, hiccup etc). While it is a word that is hard to hear initially, and these substitutes are more pleasant, or cute even, I have found that I don’t want to run from something just because it is unpleasant and it sounds intimidating. I want to face it down, to stare directly into it until I am virtually unfazed when it occurs. This does not mean that it never gets to me, or that I am completely unaffected by failure. This just means that I have have accepted failure’s inevitability, I recognize failure as a part of the creative process and the human experience, and that I would be doing myself a disservice if I were to attempt to remove it my life.

If failure is inevitable, we need to accept it as something we have to take head on, not something to run from. Most things that are worthwhile pursuing require some level of failure and learning from that failure. When we combine failure with evaluation and readjustment, we get results. Failure tells us what we did wrong, and if we can manage to not beat ourselves up over it, we can use that information to change our behavior and improve.

This brings me to the Michael Jordan quote above. I love this quote for that very reason. You don’t even have to be a sports fan to appreciate this statement. If you can apply it to your own endeavors, in this instance learning a musical instrument, it can change the way you view failure. It made me think in terms of facing failure and continuing, using it as a tool for my betterment rather than a source of shame. “I’ve failed over and over again in my life. And that is why I succeed”. This doesn’t mean that failure is going to feel great, it might still sting. It might still make you feel small. But maybe it will change the way you respond to it in the wake of its occurrence, and that is where the difference can be made.

This totally applies to learning a musical instrument. We are chasing something. We sit in awe of the musicians we admire and are inspired to take action and begin to learn, only to realize it is not as easy as we thought. Now we can either let this scare us off, or we can think of it like a science experiment. Instead of being discouraged, if we learn to fall in love with the process we can instead take a deeper look into what we are doing; working on different ways of practicing the same thing, shifting our focus to what are various limbs and digits are doing, adding and subtracting different parts to see how it changes with figure we are working on. How can I do this differently? What kind of affect did this change have when implemented? Was our hypothesis supported or was the result yielded different than we initially thought? Instead of chasing end results, by falling in love with the process of learning we make the experience of learning fulfilling on its own, and the chances of success and longevity in a given field increase.

I understand how it feels to be a student. You walk in to a room with a person who has a decade, or several decades experience on you, and it can feel intimidating. Since I realize this, I have tried to at some point demonstrate to my students something that I am starting to work on, and how I am still not quite comfortable with it yet.

My latest example has been my most recent endeavor into the world of recording. I have had some experience recording a while back, but I have not delved into the world of computer based recording software until a few weeks ago.

I have wanted to do this for a while. And even though I have finally gotten everything together to have a modest recording setup to record my drums, I knew that there was much to understand about how to record (types of microphones and their uses, how to use eq, compression, reverb, gating, room acoustics, how to deal with phasing, just to name a few). Since acquiring a minimal setup, I have done some experimenting and have roughly 3 recordings that I have tinkered with.

The first test recording I sent out to two friends who both run successful recording/tracking studios, one here in Tucson, the other back in New York. I was just excited to have something I could record and mix with, and I wanted some feedback to get better. Of course you always want the feedback to be good. I was hoping I would get a message back that said “Dude! Sounds great! Great drum sound for such a modest set up!”

As you may have guessed, that is not the response I got. The first message I got back from the friend here in Tucson was something along the lines of “Are you adding all that reverb to the mix? Too much reverb man! Hahaha! I would bring the reverb way down, and use a more natural, minimal eq approach. Also try raising your overhead microphone, the ride cymbal is pretty loud in the mix.” My New York friend gave me some of the same advice, he also added “Listen to similar records side by side with your recordings and try to mimic them. Watch videos on Youtube about recording. Always check for phase. Scour the internet and pick your friends brains to find the information you need.” It wasn’t the answer I was hoping for, but it was valuable feedback.

I did another recording. This time I raised the overhead mic, and tracked again, did some research on how to use eq, and went a little easy on the compression. The track sounded a little better, however not where I wanted it to be. I was still getting phasing (when the sound waves hit microphones at two different times and cancel each other out, causing a thinning of the sound) due to the fact my drums were set up next to a wall with no acoustic treatment and the slap back from the wall was causing the phasing in the mic, and my single overhead microphone was not cutting it quality wise. Nonetheless, I sent it to the New York friend. “It sounds better, but it still sounds like things are phasing, and now that you have raised the overhead, I can’t hear the snare as well.”

I went to Walmart and got some cheap moving blankets to treat the room with, and I also moved my drums away from the wall. I did some research and got a pair of condenser microphones my friend recommended. I hit record again.

This one was exponentially better than the first two. I eliminated the phasing problem by moving away from the wall and adding some acoustic treatment to the room. I got better microphones with better frequency response, and since I got a pair of condenser mics I was able to capture a stereo recording of my drum kit. I used the new knowledge I had learned about eq, decided to use a minimal reverb, and actually forego the compression to get a more natural sound. I sent this file to another Tucson friend, and he sent a message back that said “Sounds great man”.

Now you don’t have to be super familiar with all the recording terminology used to see that there was incremental improvement made using what I learned from each of my failures.

I have since played these tracks chronologically for many of my students, as well as shared the story that goes along with it. I started doing this initially because I was excited and wanted to expose students to the recording/production side of music (which is slowly becoming a requirement if you are going to be a musician), but I also wanted to show them that there is always going to be something that you need to work toward no matter your age or level of experience.

There is always something to learn, and with learning comes the inevitable failures that we have been discussing. It wasn’t fun for me to hear my recordings weren’t up to snuff, it initially made me feel small to be perfectly honest. I felt like a little kid that didn’t know anything again! However, through my failures there were adjustments made with the acquisition of new information, resulting in noticeable improvements. And you know what? Even though I felt ashamed I didn’t do better right off the bat, even though I had to research and learn about recording and mixing techniques, even though I had to make multiple attempts and adjustments, I still actually enjoyed the process and found it to be engaging, interesting and fulfilling. If I had let my previous failures discourage me rather than teach me, I would have never gained the understanding I have now about recording. And I still have A TON to learn about recording. Much like learning an instrument, it seems to be a pursuit without end.

I’ve failed over and over again in my life. And that is why I succeed.

Born and raised in Bridgeport Connecticut, Joshua is a newcomer to the Tucson area. Back east , he was active on the gigging scene, playing throughout Connecticut as well as some of the most popular venues in New York City for jazz and experimental music. Being a in demand freelance player, he is very knowledgeable in a variety of styles, and approaches them with respect, whatever the genre. Through learning these many styles he has formed an interesting way of expressing himself on the instrument, whether it be playing in a straight ahead jazz context, working with a Rock/Pop group, or even playing modern R&B and Hip Hop. He has done playing home and abroad, in Connecticut, New York, and California, to Morocco and Bermuda! Teaching has always been a big part of what he does. Having taught at many local studios and taught many private lessons in the Connecticut and New York area, he has a ton of experience in conveying ideas to students new to the drums, of all ages. He feels teaching is a big part of the experience of being a musician, and loves to share his knowledge with as many people as he can. Joshua is really passionate about sharing his love for the instrument, and helping people develop their unique way of musically expressing themselves. He’s happy to bring his experience and knowledge to Allegro!